Multidimensional Spaces

Introduction

We live in a three-dimensional space. It is so familiar to us that the properties of spaces with a higher number of dimensions often turn out to be very unexpected. Nevertheless, it is precisely such spaces that are encountered in machine learning, where objects are usually characterized by n real-valued features. Let us consider some mathematical aspects of high dimensionality.

Hypercube

By normalization, it is always possible to ensure that the value of each feature lies in the interval from 0 to 1. Then all objects can be represented as points inside an n-dimensional unit hypercube in feature space.

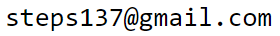

The unit 2-dimensional cube (a square in the plane) has 4 vertices with coordinates

(0,0), (0,1), (1,0), (1,1).

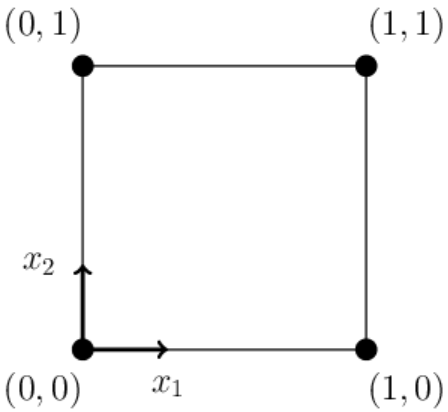

A 3-dimensional cube has 8 vertices.

The unit 2-dimensional cube (a square in the plane) has 4 vertices with coordinates

(0,0), (0,1), (1,0), (1,1).

A 3-dimensional cube has 8 vertices.

In an n-dimensional space: x = {x1,...,xn}. Let one vertex of the cube be at the origin: {0,0,...,0} (n zeros). The remaining vertices are enumerated by all possible sequences of n zeros and ones: {0,0,...,0}, {1,0,...,0}, ..., {1,1,...,1}, therefore:

An n-dimensional hypercube has 2n vertices

For large n, the hypercube becomes a very "spiky" object. For example, when n=32, it has 4'294'967'296 vertices.

From each of the $2^n$ vertices of the hypercube, $n$ edges emerge (for the vertex (0,0,...,0) these are the $n$ coordinate axes). Therefore, the total number of edges of the hypercube is $n\,2^n/2=n\,2^{n-1}$.

The diagonal connecting the points {0,0,...,0} and {1,1,...,1}, has length $\sqrt{n}$ (there are $n$ such long diagonals). A "face" of the hypercube is an $(n-1)$-dimensional cube with $2^{n-1}$ vertices (a 3-cube has 6 square faces). There are $2\,n$ such faces in a hypercube. In addition, a hypercube can be obtained by connecting with edges the vertices of two $(n-1)$-dimensional cubes (for an "ordinary" cube, these are two squares). In this case, we again obtain:

Compactness hypothesis

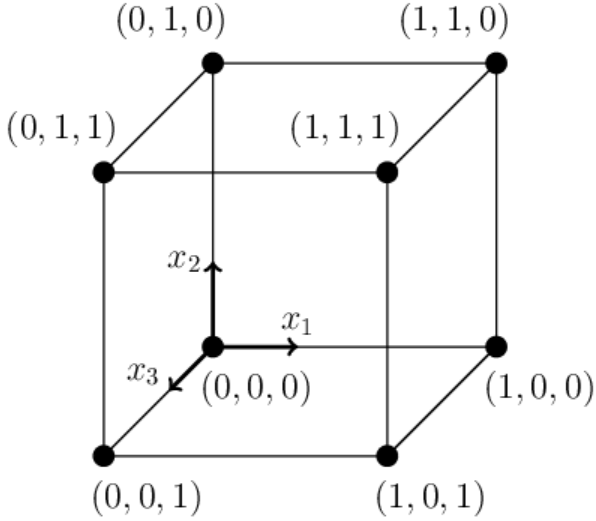

Suppose we want to uniformly fill the feature space inside a hypercube with points (training samples).

To do this, we divide each feature (axis) into k equal parts.

As a result, we obtain kn small cubes, each of which can contain one point.

It is clear that even for k = 2

and n = 32, this is practically impossible.

Thus, a high dimensional space is

very large.

Suppose we want to uniformly fill the feature space inside a hypercube with points (training samples).

To do this, we divide each feature (axis) into k equal parts.

As a result, we obtain kn small cubes, each of which can contain one point.

It is clear that even for k = 2

and n = 32, this is practically impossible.

Thus, a high dimensional space is

very large.

It is necessary to strive for such a selection of object features that the representations corresponding to their classes are not overly complex. This is sometimes formulated as the compactness hypothesis:

Each class should occupy a relatively compact region in an n-dimensional space, so that different classes are separable from one another by relatively simple surfaces (ideally hyperplanes).Otherwise, not only the recognition task, but even the preparation of the training set becomes a very non-trivial problem.

Ball

The set of points that are equidistant from a given point (the center) is called a sphere. The space inside a sphere is called a ball. A ball inscribed in a hypercube is a very "small" object. In an $n$-dimensional space, a ball of radius $R$ has the following volume $V_n$ and surface area $S_n$: $$ V_n = C_n\cdot R^n,~~~~~~~~~~~~S_n = C_n\cdot n\,R^{n-1},~~~~~~~where~~~~~~C_n = \frac{ \pi^{n/2} }{\Gamma({n\over 2}+1)},~~~~~C_{2k} = \frac{\pi^k}{k!} $$ Here $\Gamma(x)$ is the gamma function: $\Gamma(1)=1,~~~$ $\Gamma(1/2)=\sqrt{\pi}$, $~~\Gamma(z+1) = z\,\Gamma(z)~~$ and $~~\Gamma(z+\alpha)=z^\alpha\,\Gamma(z)$ for $z \gg 1$.

A ball of radius R=1/2 can be inscribed into the unit hypercube. Its volume for n=10 is V10=0.0025, and for n=32 it becomes vanishingly small: V32=10-15. Although the ball "touches" the faces of the hypercube, it is surrounded by a huge number (2n) of corners.

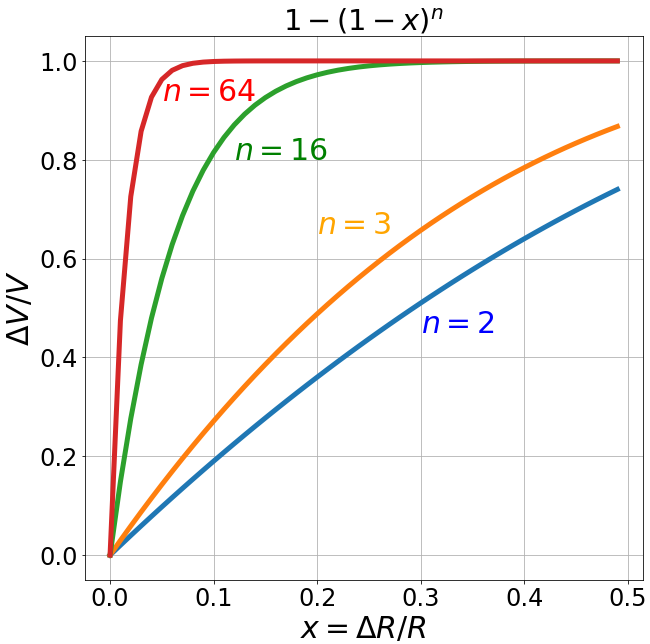

Another remarkable property of an n-dimensional ball is that almost all of its volume is concentrated near the surface.

Indeed, consider two nested balls with radii $R$ and $R-\Delta R$.

The difference of their volumes equals the volume of the spherical shell between them:

$$

\frac{\Delta V}{V} = \frac{R^n - (R-\Delta R)^n}{R^n} = 1 - \left(1-\frac{\Delta R}{R}\right)^n.

$$

The ratio of the shell volume to the volume of the ball of radius $R$

is shown in the figure on the right for different space dimensions $n$.

Another remarkable property of an n-dimensional ball is that almost all of its volume is concentrated near the surface.

Indeed, consider two nested balls with radii $R$ and $R-\Delta R$.

The difference of their volumes equals the volume of the spherical shell between them:

$$

\frac{\Delta V}{V} = \frac{R^n - (R-\Delta R)^n}{R^n} = 1 - \left(1-\frac{\Delta R}{R}\right)^n.

$$

The ratio of the shell volume to the volume of the ball of radius $R$

is shown in the figure on the right for different space dimensions $n$.

Assume that the ball is uniformly filled (with constant density) with objects. A randomly selected object (for large $n$) will almost certainly be located near the surface of the ball.

Suppose that objects of a given class are characterized by some typical (mean) feature values with a small spread around these means. Then the representation of this class corresponds to the center of a ball in an n-dimensional space. The smaller the spread around the mean, the smaller the radius of such a class-ball. If different features have different spread amplitudes, the ball turns into an ellipsoid. By a linear transformation, any ellipsoid can always be transformed into a ball. However, if several different ellipsoids exist in the feature space, a linear transformation can convert only one of them into a ball.

Embedding spaces

When processing texts or images, feature vectors are obtained for which cosine distance is used as the measure of similarity. In this case, it is more convenient to consider the unit-radius sphere as the basic object. For even $n$, its volume is: $$ V_2=3.14,~~~~~~~V_{16}=0.23,~~~~~~~V_{32}=4\cdot 10^{-6},~~~~~~~V_{64}=3\cdot 10^{-20},~~~~~~~~V_n=C_n=\frac{\pi^{n/2}}{(n/2)!}. $$

For unit vectors lying on the sphere, the square of the Euclidean distance between them

is proportional to their cosine distance:

For unit vectors lying on the sphere, the square of the Euclidean distance between them

is proportional to their cosine distance:

$$ D(\mathbf{x},\mathbf{y}) = (\mathbf{x}-\mathbf{y})^2 = \mathbf{x}^2 + \mathbf{y}^2 - 2\,\mathbf{x}\cdot \mathbf{y} $$ $$ D(\mathbf{x},\mathbf{y}) = 2\,\bigr(1-\cos(\mathbf{x},\mathbf{y})\bigr). $$

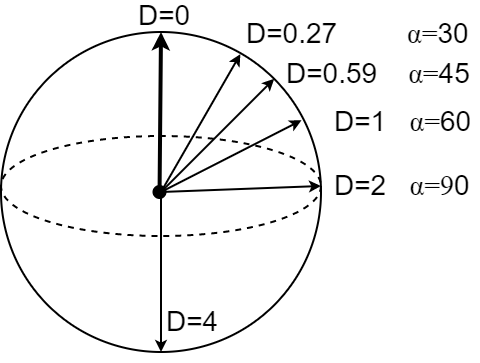

If, on the "surface" of an

$(n-1)$-dimensional hypersphere, we draw an $(n-2)$-dimensional sphere of radius $r$, then the ratio

of the hypersphere surface area to the volume of the sphere is on the order of:

$$

\frac{S_n(R)}{V_{n-1}(r)} \approx \sqrt{2\pi n}\, \left(\frac{R}{r}\right)^{n-1}

$$

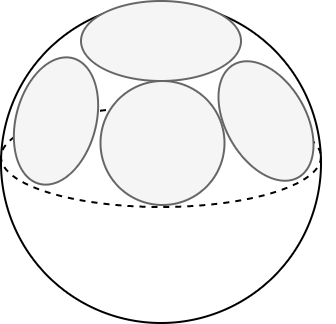

Thus, on a unit $n$-hypersphere $R=1$ let's draw an ($n-1$)-sphere of radius $r=1/2$ (half a radian or 28°).

Then, in a 100-dimensional space, the number of such non-overlapping spheres can be on the order of $2^{100}$.

Consequently, they can accommodate clusters of objects from different classes. High-dimensional space is significantly more "capacious".

$$

\frac{S_n(R)}{V_{n-1}(r)} \approx \sqrt{2\pi n}\, \left(\frac{R}{r}\right)^{n-1}

$$

Thus, on a unit $n$-hypersphere $R=1$ let's draw an ($n-1$)-sphere of radius $r=1/2$ (half a radian or 28°).

Then, in a 100-dimensional space, the number of such non-overlapping spheres can be on the order of $2^{100}$.

Consequently, they can accommodate clusters of objects from different classes. High-dimensional space is significantly more "capacious".

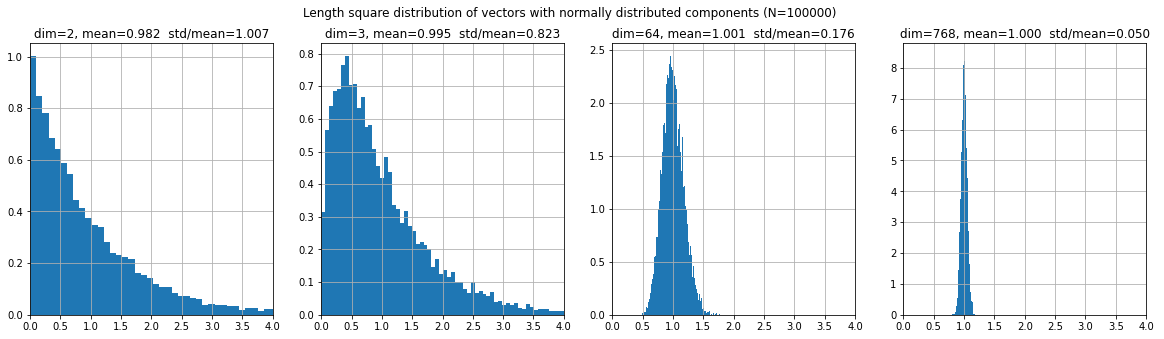

If the components of a vector are random Gaussian variables $\varepsilon$ with zero mean and unit variance, then the expected value of the squared length of the vector equals the dimensionality of the space: $$ \langle \mathbf{x}^2\rangle = \langle \varepsilon^2_1+...+\varepsilon^2_1\rangle = n. $$ At the same time, for large $n$ the probability distribution of the squared length $D=\mathbf{x}^2$ has a narrow peak in the neighborhood of $n-2$ (all points "concentrate" near the sphere):: $$ \frac{e^{-(\varepsilon^2_1+...+\varepsilon^2_n)/2}} {(2\pi)^{n/2}}\, d\varepsilon_1...d\varepsilon_n = \frac{\Omega_n}{(2\pi)^{n/2}}\, e^{-r^2/2}\, r^{n-1}\,dr = \frac{\Omega_n}{2(2\pi)^{n/2}}\, e^{-D/2}\, D^{n/2-1}\,dD $$ Let's simulate this using the numpy library:

X = np.random.normal(0.0, 1, (10000, dim))/dim**0.5 R2 = (X*X).sum(axis=1)

m-dimensional planes

Let $\mathbf{x}=\{x^1,...,x^n\}$ be a point in an $n$-dimensional space (the superscript denotes the coordinate index). A surface of dimension $m$ can be described parametrically as $$ \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{f}(t_1,...,t_m), $$ where $t_k$ is a set of scalar parameters (their number equals the dimension of the surface). For example, the unit sphere in 3-dimensional space is described by 2 angles $\{t_1,t_2\}=\{\theta,\phi\}$: $$ x = \sin \theta \cos\phi, ~~~~~y = \sin \theta \sin\phi,~~~~~z = \cos \theta. $$ The simplest $m$-dimensional surface is a plane. Let $\mathbf{e}_k=\{\mathbf{e}_1,...,\mathbf{e}_m\}$ be a set of $m$ unit, pairwise orthogonal vectors ($\mathbf{e}_k\mathbf{e}_p=\delta_{pk}$, where $\delta_{pk}$ is the Kronecker symbol). Then the equation of the plane has the form \begin{equation}\label{plane_eq} \mathbf{x}= \mathbf{x}_0 + \sum^m_{k=1} t_k\mathbf{e}_k. \end{equation} The parameters $\{t_1,...,t_m\}$ act as Cartesian coordinates in an $m$-dimensional space with basis $\{\mathbf{e}_1,...,\mathbf{e}_m\}$. The vector $\mathbf{x}_0$ specifies the position of the origin (a point in the $n$-dimensional space at which all plane coordinates $t_k$ are zero). Equation (\ref{plane_eq}) is the first-order term of the Taylor expansion of an arbitrary surface $\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{f}(t_1,...,t_m)$ in a neighborhood of the point $t_1=...=t_m=0$. If $m=1$, then (\ref{plane_eq}) describes a line (a one-dimensional object). For $m=2$ we obtain a two-dimensional plane, and so on.

Distance to an $m$-plane

Let's derive an expression for the shortest Euclidean distance $(\mathbf{x}-\mathbf{X})^2$ from an arbitrary point $\mathbf{X}$ to the $m$-plane (\ref{plane_eq}). To do this, we need to find the parameters $t_k$ that minimize this distance: $$ d^2 = \bigr(\mathbf{x}_0-\mathbf{X} + \sum^m_{k=1} t_k\mathbf{e}_k\bigr)^2 = \min. $$ Taking the derivative with respect to $t_p$, setting it to zero, and using the orthonormality of the vectors $\mathbf{e}_k$, we obtain: $$ \bigr(\mathbf{x}_0-\mathbf{X} + \sum^m_{k=1} t_k\mathbf{e}_k\bigr)\,\mathbf{e}_p = (\mathbf{x}_0-\mathbf{X})\,\mathbf{e}_p + t_p = 0 ~~~~~~~~\Rightarrow~~~~~~~t_p = -(\mathbf{x}_0-\mathbf{X})\,\mathbf{e}_p. $$ Substituting these $t_p$ into the squared distance $d^2$ we get: $$ d^2 = \bigr(\mathbf{x}_0-\mathbf{X} - \sum^m_{k=1} \bigr[(\mathbf{x}_0-\mathbf{X})\,\mathbf{e}_k \bigr]\,\mathbf{e}_k\bigr)^2. $$ Expanding the square (again using orthogonality), this expression can be rewritten as: \begin{equation}\label{d2_to_plane} d^2 = \bigr(\mathbf{x}_0-\mathbf{X}\bigr)^2 - \sum^m_{k=1} \bigr[(\mathbf{x}_0-\mathbf{X})\,\mathbf{e}_k \bigr]^2. \end{equation} The projection of the point $\mathbf{X}$ onto the plane is obtained by substituting the optimal parameters $t_k$ into the plane equation (\ref{plane_eq}): \begin{equation}\label{projec_coord} \mathbf{X} ~\mapsto~\mathbf{x}=\mathbf{x}_0 + \sum^m_{k=1} \bigr[(\mathbf{X}-\mathbf{x}_0)\,\mathbf{e}_k\bigr]\mathbf{e}_k. \end{equation}

Hyperplane

A hyperplane in an $n$-dimensional space is an $m=(n-1)$-dimensional plane. (in 2D this is a line, and in 3D it is an "ordinary" plane). A hyperplane can always be drawn through $n$ points. Accordingly, it is defined by $n$ parameters (for example, by a unit normal vector ($\boldsymbol{\omega}^2=1$) perpendicular to the plane $\boldsymbol{\omega} = \{\omega^1,....,\omega^n\}$ and a bias (offset) parameter $\omega_0$.

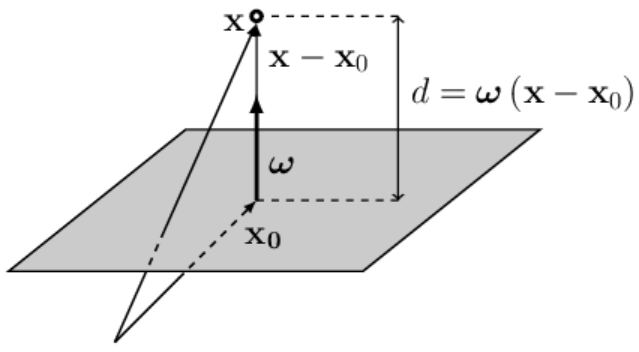

Let the hyperplane pass through the point $\mathbf{x}_0$ and have the normal vector $\boldsymbol{\omega}$. Then the distance d from the hyperplane to a point $\mathbf{X}=\{X^1,...,X^n\}$ is calculated by the formula

$$ d = \omega_0 + \boldsymbol{\omega}\mathbf{X},~~~~~~~~~~~~\omega_0 = -\boldsymbol{\omega}\mathbf{x}_0. $$Here $d > 0$ if the point $\mathbf{X}$ lies on the side of the plane toward which the vector $\boldsymbol{\omega}$ points, and $d < 0$ if it lies on the opposite side. When $d=0$, the point $\mathbf{X}$ lies on the plane. Changing the parameter $\omega_0$ shifts the plane parallel to itself in space. If $\omega_0$ decreases, the plane moves in the direction of the vector $\boldsymbol{\omega}$ (the distance becomes smaller), and if $\omega_0$ increases, the plane moves opposite to the direction of $\boldsymbol{\omega}$. This follows directly from the formula above.

◄

Let's write the vector $\mathbf{X}-\mathbf{x}_0$, which starts at the point $\mathbf{x}_0$

(lying on the plane)

and points toward $\mathbf{X}$ (vectors are added according to the triangle rule).

The point $\mathbf{x}_0$ is chosen at the base of the vector $\boldsymbol{\omega}$,

therefore $\boldsymbol{\omega}$ and $\mathbf{X}-\mathbf{x}_0$ are collinear (lie on the same line).

If the vector $\boldsymbol{\omega}$ is unit ($\boldsymbol{\omega}^2=1$), then the scalar product

$d=\boldsymbol{\omega}\,(\mathbf{X}-\mathbf{x}_0)$ is equal to the distance $d$ from the point $\mathbf{X}$ to the plane.

◄

Let's write the vector $\mathbf{X}-\mathbf{x}_0$, which starts at the point $\mathbf{x}_0$

(lying on the plane)

and points toward $\mathbf{X}$ (vectors are added according to the triangle rule).

The point $\mathbf{x}_0$ is chosen at the base of the vector $\boldsymbol{\omega}$,

therefore $\boldsymbol{\omega}$ and $\mathbf{X}-\mathbf{x}_0$ are collinear (lie on the same line).

If the vector $\boldsymbol{\omega}$ is unit ($\boldsymbol{\omega}^2=1$), then the scalar product

$d=\boldsymbol{\omega}\,(\mathbf{X}-\mathbf{x}_0)$ is equal to the distance $d$ from the point $\mathbf{X}$ to the plane.

If the length $\omega=|\boldsymbol{\omega}|$ of the vector $\boldsymbol{\omega}$ is not equal to one, then $d$ is $\omega$ times larger ($\omega > 1$) or smaller ($\omega < 1$) than the Euclidean distance in the $n$-dimensional space. When the vectors $\boldsymbol{\omega}$ and $\mathbf{X}-\mathbf{x}_0$ are oriented in opposite directions, we have: $d < 0$. ►

If the space has n dimensions,

then a hyperplane is an (n-1)-dimensional object.

If the space has n dimensions,

then a hyperplane is an (n-1)-dimensional object.

It divides the entire space into two parts.

For clarity, consider a 2-dimensional space.

A hyperplane there is a straight line (a one-dimensional object).

In the figure on the right, a circle represents one point of the space,

and a cross represents another. They are located on opposite sides of the line (the hyperplane).

If the length of the vector ω is much greater than one, then the absolute values of the distances

d

from the points to the plane will also be much larger than one.

The equation of a hyperplane, similarly to an $m$-plane, can be written in parametric form using $n-1$ basis vectors $\{\mathbf{e}_1,...,\mathbf{e}_{n-1}\}$. All these vectors are orthogonal to the normal vector: $\boldsymbol{\omega}\mathbf{e}_k=0$.

Simplex

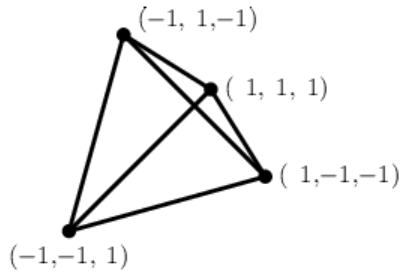

A simplex is an n-dimensional generalization of a triangle in a 2-dimensional space.

In 3 dimensions it is a tetrahedron (figure on the right).

A hyperplane can be drawn through n points in an n-dimensional space.

Accordingly, n+1 points in the general case do not lie on one hyperplane

and form a simplex with n+1 vertices. If all edges (distances between pairs of vertices)

are equal, the simplex is called regular.

Opposite each of the n+1 vertices there lies a hyperplane (on which this vertex does not lie).

A simplex is an n-dimensional generalization of a triangle in a 2-dimensional space.

In 3 dimensions it is a tetrahedron (figure on the right).

A hyperplane can be drawn through n points in an n-dimensional space.

Accordingly, n+1 points in the general case do not lie on one hyperplane

and form a simplex with n+1 vertices. If all edges (distances between pairs of vertices)

are equal, the simplex is called regular.

Opposite each of the n+1 vertices there lies a hyperplane (on which this vertex does not lie).

Each of the $n+1$ vertices of the simplex is connected to all other vertices by edges. Accordingly, the number of edges is equal to $n\,(n+1)/2$.

The volume of a regular simplex with unit edges is equal to: $$ V_n = \frac{\sqrt{n+1}}{n!\,2^{n/2}}. $$ Like a ball, this is a very “small” object.

Let objects of one class be located inside a sphere, and objects of another class be located outside it. To separate them, a neural network with one hidden layer will be required, having at least n+1 neurons in the hidden layer. They form n+1 hyperplanes of the simplex (possibly with smoothed corners if the lengths of the normal vectors are small).

A little bit of math

Similarly, for three-dimensional space $d^3x = r^2 dr\,d\Omega$, therefore $V_3=(4/3)\pi R^3$ and $\Omega_3=4\pi$.

For the $n$-dimensional case, let's compute the product of $n$ Gaussian integrals ($r^2=x^2_1+...+x^2_n$): $$ \int\limits^\infty_{-\infty} e^{-(x^2_1+...+x^2_n)}\, d^n x = \int\limits^\infty_{0} e^{-r^2}\, r^{n-1}\,d r \int d\Omega = \frac{1}{2}\,\Gamma(n/2) \int d\Omega = \pi^{n/2}, $$ where the last equality is obtained by raising the Gaussian integral (the first integral) to the $n$-th power. Now it's easy to write the $n$-dimensional solid angle and the volume of an $n$-dimensional sphere of radius $R$: $$ \Omega_n = \int d\Omega= \frac{2\,\pi^{n/2}}{\Gamma(n/2)},~~~~~~~~~~~~~V_n = \frac{\Omega_n R^n}{n}. $$